Former English teacher wanders into literary stardom

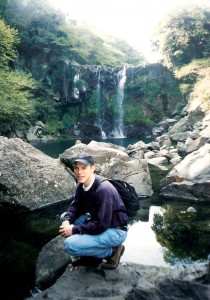

Meet Rolf Potts, the Jack Kerouac of the Internet age.

But while the beat generation had to be content to read of Kerouac’s road tales in a bulky years-after-the-fact compilation, fans of Potts’ “Vagabonding” column at Salon get to ride shotgun on the twentysomething American’s wild yet culturally adept adventures through the bargain travel destinations of the world.

“This would have been impossible without the Internet,” wrote Potts in an interview conducted with The Korea Herald through a series of e-mails posted from Cairo, Galilee, Beirut and Kansas. “Snail submissions and the cost of all those phone calls to my editor would have eventually driven me into poverty or insanity.”

Potts’ online fame has not gone unnoticed by older mediums. He now phones in frequent dispatches to America’s National Public Radio and fields frequent requests for stories from the editors of glossy travel magazines.

In 2000 Potts finds himself on the cusp of literary stardom. This year his Salon essays have been honored with selections by no less than four travel writing anthologies, including the forthcoming debut of Houghton Mifflin’s The Best American Travel Writing, which will include P.J. O’Rourke and William T. Vollman.

And to think, Potts literary wanderings began in The Korea Herald‘s “In My View” section.

Well, not exactly. But before being discovered by Salon, in 1997, Potts, while temporarily rooted in Pusan working as an English teacher, published two essays on the Herald‘s opinion page. The first, “In Defense of Living Nowhere” laid some of the groundwork for what has evolved into his now famous vagabonding ethic. The second, “Ich Bin Ein Sidewalker,” compared the dangers of the DMZ with the perils of walking the streets of Korea’s No. 2 city.

“Neither article was stellar writing,” said Potts. “But it was good to be published at that point in my career.”

The next few essays he wrote about his life in Pusan were e-mailed to Salon, which took them all. While the topics varied from student protests to fortune tellers, all explored a phenomenon which previously had been dealt with only in the reader’s forum sections of Korea’s English-language papers: the droves of North Americans flocking to the former Hermit Kingdom to teach English conversation for fun and profit.

“Perhaps at no time in history had so many young Americans been making so much money in a foreign country with absolutely no grasp of the native language or customs,” wrote Potts in the final installment in the series, his opus, “Letter from Pusan: the party’s over.” The essay detailed the fall of the city’s once thriving expat community in the wake of the IMF crisis.

The party may have been over for Pusan, but for Potts it was just beginning. He had been squirreling away his won and had been lucky enough to cash out before Korea’s currency imploded.

Potts headed to Southeast Asia, traveling through Thailand, Cambodia and Laos. He kept sending more stories to Salon which they kept taking. Eventually, he pitched an idea for a column: “Vagabonding into the Millennium,” a backpacker’s chronicle. The rest is road history.

From the start, Potts’ vagabond existence was about more than collecting stamps for his passport and war stories to share with his buddies back home. Like Kerouac, Potts is not interested in plotting a steady course. And like the beats, he possesses a nascent yet powerful philosophy of road life which he tests at every destination.

But unlike Kerouac, Potts finds his road nearly gridlocked with people a lot like him.

“With world travel turning into one big, grudging egalitarian democracy, we are compelled to aspire to a greater ethic in our wandering,” wrote Potts in one essay analyzing the phenomenon of Khao San Road, Thailand’s infamous backpacker’s ghetto. “Defining how we travel, in effect, has become a matter of individualist self-perception: It has become inseparable from how we define ourselves.”

From Southeast Asia, he headed north to China and Mongolia where he then embarked on his epic East-West crossing. (See “The Trans-Siberian Toilet War of 1999” at Salon.) After road tripping south through Eastern Europe, the dawn of the new millennium found him in Corfu, Greece. At present, he is still vagabonding, his most recent essay being posted from Beirut, detailing a brief friendship with an overbearing detergent tycoon who tried to bully him into becoming a PR spokesman for the new Lebanon.

Potts says such small, yet poignant non-adventures are what he is after: “In vagabonding, I seek to find adventure in the normal and normalcy within adventure. It’s a simple, yet remarkably effective strategy.”

Potts plans to stay mobile until early next year, whereupon he will return to the United States to hammer out a memoir of his travels. He is looking forward to another “reverse-sabbatical” – a short rest from the road to work to build up funds for more wandering.

“My life is very rich in experience, but poor in permanence,” said Potts. “I miss not having a familiar place to sit down every once in a while. I get tired of wearing the same five sets of clothes all the time. But these are sacrifices I’ve gotten used to, and I have no regrets.”

Category: Travel Writing