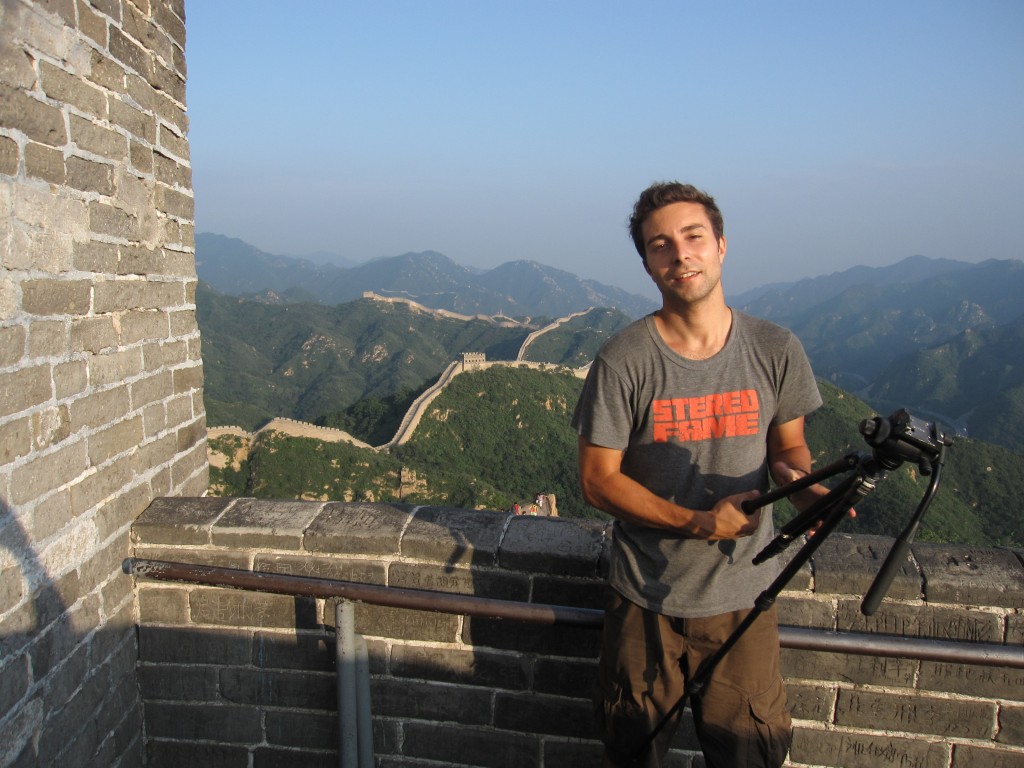

Q&A with Brook Silva-Braga, director of ‘The China Question’

China is a huge country, and an even bigger topic to tackle in a movie. Filmmaker Brook Silva-Braga took on that daunting challenge in his new documentary, “The China Question.” This is the divisive issue that causes American workers to worry, politicians to vacillate, and businesspeople to make deals: “What does China’s rise mean for America?”

Marcus Sortijas, Vagablogging’s Asia beat editor and creator of the Marcus Goes Global blog, interviewed Brook about his film, China, and the vagabonding life.

Trailer for “The China Question”:

What was the catalyst that got you started on this project?

In a way, it started with my mom actually, because she has been boycotting “Made in China” products for years now. I think most Americans have a sense that we’re helping China become more powerful and that China has pretty different values and priorities than we do.

But I kind of wondered whether my mom was on to something or was just being really naïve. So even though her boycott wasn’t the reason I went to China, it did provide a kind of frame to look through: “How does what’s happening in China affect us and how should we respond?”

Can you briefly describe your professional background?

Well I studied journalism at New York University and then got a job as a producer for HBO Sports. After a few years of that I quit to go on an around-the-world trip. While I was out there, I shot the backpacking documentary “A Map for Saturday.” The movie did well enough for me to launch a production company and keep making independent docs.

In “A Map for Saturday,” you did a trip around the world. How did your experience as a vagabonder help you film “The China Question”?

The experience as a vagabonder is a huge asset for my style of filmmaking. As a vagabonder I travel very light and very cheap, which makes it possible economically to do these types of projects. Using a normal production model, no documentary could afford 100-foreign-shoot days like I had on this project.

But it also helps with content because when you’re literally sleeping on someone’s floor you get a different interview with them than you would by just meeting in an office, shaking hands and hitting ‘record.’

How did you prepare for your trip to China? Any advice for people planning to go?

I tried to make friends through Couchsurfing and that was pretty useful, not just for free places to stay but more so to find English speakers. China is a huge country that rewards extended trips, the longer you have the more interesting your experience will be because there’s so much to see outside Shanghai and Beijing.

What were the most difficult obstacles to shooting and traveling in China?

When you get away from the industrialized east coast the level of development plummets and even having a Mandarin translator doesn’t help much, since most people just speak their local dialect.

The distances also get really long, so 12 to 18-hour bus rides are typical out west. But to be honest, as I look back at it now I mainly remember all the great parts and have forgotten the headaches.

Could you share any stories about your worst and best moments traveling in China?

Man there were a lot. One crazy one involved being approached by some women in a park in Ningbo. They wanted my girlfriend and I to model for their photo studio.

In China, couples spend thousands of dollars to take elaborate wedding photos long before they’re actually married. The studio offered to shoot us for free if they could use the images in their portfolio. So the next day they dressed us up in some gaudy formalwear and paraded us around Ningbo taking “wedding” photos. The whole thing was pretty hilarious.

Did you also do post-production in China?

I did the post-production back in the U.S. One thing that sets this film apart from “A Map for Saturday” and “One Day in Africa” is that it has a strong American component. I spent lots of time road-tripping across the U.S. to get that perspective as well. Then I sat with all my footage back in New York and cobbled it together.

From talking to Americans around the country, what were their views on China?

Overall there’s just a sense that China is eating our lunch and people have different thoughts on why that’s happening and different levels of understanding about the forces at play. But there is a pretty broad pessimism about it. What’s a bit surprising–and what I hope the movie will help change–is there isn’t all that much talk about what concrete steps we should take to create a more favorable situation.

You interviewed a wide range of people: workers on both sides, scholars, normal people, and of course, your own mother. One group was conspicuously absent: American CEOs. Can you explain why?

One of the surprises of the project for me was how willing Chinese companies were to talk about the work they’re doing–they’re proud of it.

American companies aren’t quite as eager to talk about US/China trade. For starters, it’s just unpopular because it’s often associated with outsourcing. I attempted to speak with several large American companies–but they tended to suffer from schedules that were too full to speak on-camera.

What was your past experience with China and the Chinese language before this? How did that help or hinder you?

I had never been to China and didn’t know a single word of the language. The language gap was definitely a handicap. But there were at least two advantages to being a newcomer.

First, I saw China with totally fresh eyes and, second, I hadn’t invested years learning the language. So, if at the end of the project I was banned from China because of the film, that wouldn’t be so devastating. I think it made me a bit more fearless.

At one point in the film, you did say that your documentary would probably get banned in China. (Note: This was due to a segment on the 1989 Tiananmen Square protests) Has that happened? Was there any backlash from the PRC government?

The Chinese government is nothing if not savvy. By now they’ve realized that boldly condemning something only brings more attention to it, so their retribution is usually subtle.

I know a number of writers who have written gently critical books about China and found it suddenly very difficult to get a visa to enter the country. Another popular tactic is stealth attacks on their websites.

It’s too soon to know if they’ll pay me that type of attention. But it’s pretty certain my film won’t be officially welcomed into the country. Only 20 foreign films are allowed in each year.

I enjoyed how you re-visited Susu, the woman driver who served as your translator, later in the film. The young teacher in Xinjiang was also a colorful character. Have you heard any recent news from the Chinese people you spoke to?

I’m still in touch with several of them and life continues to evolve in that rapid way it does in China. The big change we see in Susu at the end of the film has continued, she is certainly no longer a driver.

Did you have any preconceived ideas about China when you started? How did your opinions change as you filmed this project?

I didn’t have any major shifts of opinion, just a much finer understanding of lots of things. When you read that it’s a fast-growing economy you may understand what that means. But then you meet someone doing manual labor and then return a year later to find them making close to six-figures in an office job. It gives you a different appreciation of what is going on.

Thank you for talking with us. Best of luck with your film.

To find out more, please visit the film’s website: The China Question.

April 8th, 2011 at 11:55 am

[…] Sortijas just posted the Q&A we did about ‘The China Question’ over on Rolf Potts’ Vagablogging site. It’s a […]

April 8th, 2011 at 2:23 pm

I’m glad someone is finally taking on this topic through film.

As for the extravagant wedding photos, I hear they are supposed to take new sets of pictures each year they’re married…it’s supposed to be good luck. Thanks for sharing your conversation with Brook Silva-Blaga. I’ll have to look into the other films he’s made. It’s great that he’s taking the chance to inform people of the situation between the US and China.

April 8th, 2011 at 7:16 pm

hey, seems like everything is made in china, but how much exactly?

Funny story about the wedding pictures episode. I can really picture that kind of thing happening in China…ha ha!

April 8th, 2011 at 9:27 pm

An eye opening blog post. Good wishes for Brook.

April 9th, 2011 at 1:02 am

This sounds like is has a lot of potential. I look forward to seeing it!

April 10th, 2011 at 4:06 pm

Chinese artist Ai Weiwei has been imprisoned. I principle isn’t a principle until it costs you something. We need to ask ourselves, collectively, what exactly are our principles?

If we refuse to purchase from companies who rely on China – in the same way many refuse to purchase from companies that are not green – the pressure will be felt, and China will feel it as well. The only reason we don’t, is we hear – seemingly, from all sides – that we must do business in and within China, no matter how misaligned with our own principles. But it’s not coming from all sides. It’s 90% of corporate media and industry, which is who stands to gain, that inundates us with that rhetoric. But as a people, we can choose to exert pressure that affects change. The world economy will not ‘collapse.’ It will adjust to find a way to grow, and that adjustment will be in the form of pushing for what’s right.

April 11th, 2011 at 2:22 am

I somewhat agree with Jason; the economy will adjust to a balance. Based on this, it seems that currently China is where the economic advantages go. Does this mean that the United States has to find its advantages or create one? As Brook Silva-Braga said, “there isn’t all that much talk about what concrete steps we [people in the United States] should take to create a more favorable situation.” Sitting there doing nothing does not help. It should be good that the United States finds its own goods and competes with China in economy, and competitions often lead to a better quality for things, especially for developed countries such as the United States.